ALL THE TIME IN THE WORLD

Design Museum Den Bosch, 's-Hertogenbosch, The Netherlands

5 April – 25 August 2025

Curated by Tomas van den Heuvel

Dries Depoorter, Hendrick Goltzius, Petrus van Kessel, Joep van Lieshout, Maarten Baas, Susan Morris and Matsuo Miyajima

PRESS RELEASE

‘How are you?’ - ‘Yeah, good! Busy!’ Time, or the lack of it, has become a status symbol. The mechanical measurement of time revolutionised our society. The clock controls our daily rhythm, the calendar defines our lives. Productivity apps and gurus encourage us to plan for every minute of the day. Imagine missing out on something!

Time is a mysterious phenomenon that has fascinated scientists, philosophers and artists for centuries. At the same time, it is a social and cultural construct. How we measure time betrays our position in society. Lavishly decorated clocks were once reserved for the very rich. By contrast, in our day and age it is a great luxury to not have to keep an eye on the clock. Not so long ago, trade unions fought hard for an eight-hour working day; now there are even calls for a working day of only six hours.

Time, on reflection, does not seem to be as objective as the numbers on the clock suggest. How do we measure time, and more importantly, how do we shape it? What does it actually mean to be productive, or to make the most of your day? The exhibition All the Time in the World stops the clocks for a moment, to take a closer look at time.

Featuring work by contemporary artists including Susan Morris, Maarten Baas, Dries Depoorter, Joep van Lieshout and Tatsuo Miyajima, alongside historical and designer objects by Bruno Ninaber van Eyben, Meret Oppenheim, Cartier, Omega, Hendrick Goltzius and Petrus van Kessel amongst many others.

TIME IS ALSO DESIGN, article by Marloes Heineke for NRC Magazine, NL, April 2025.

TRANSLATION

You could translate horloge de chair as ‘biological clock’, but ‘watch of flesh’ sounds just as beautiful. We owe the knowledge of its existence in part to Michel Siffre, a French geologist and pioneer in chronobiology. For his first groundbreaking experiment, at the age of 23 in 1962, he spent two months alone in a cave, without daylight or a clock. His only connection to the outside world was a phone, through which he reported when he ate, went to bed, and woke up. In the cave, Siffre’s sense of time quickly fell out of sync with clock time. Every time span felt much shorter, as if he was living more slowly. When he was told after two months that his time in the cave was up, he thought he still had nearly a month to go. The cave was cold and damp. Siffre hallucinated, his short-term memory began to falter, and he fell ill several times. But he didn’t notice that cave time wasn’t following clock time. On the contrary, he later said: “I slept perfectly. My body decided for itself when to sleep and eat.”

A biological clock ticks in every living being, driven by genes. In some fish and marine animals, it’s directly or indirectly linked to the lunar cycle — they ‘know’ when it’s high or low tide. The sea centipede even knows when it’s spring tide and lays its eggs only then.The human sleep-wake rhythm is controlled by the circadian cycle, which ‘circles around the day’ and lasts about 24 hours. About 24 hours — because for some people it’s half an hour shorter, and for others up to an hour longer. That’s why our biological clock needs to be reset daily; in humans, daylight takes care of that. Without this external synchronization, the clock listens only to itself, starts ‘free running,’ and the longer this continues, the more deviations accumulate. That’s what happened to Siffre. When he finally emerged — thin, unsteady, and wearing dark glasses against the daylight — it took him five minutes, instead of two, to count to 120.

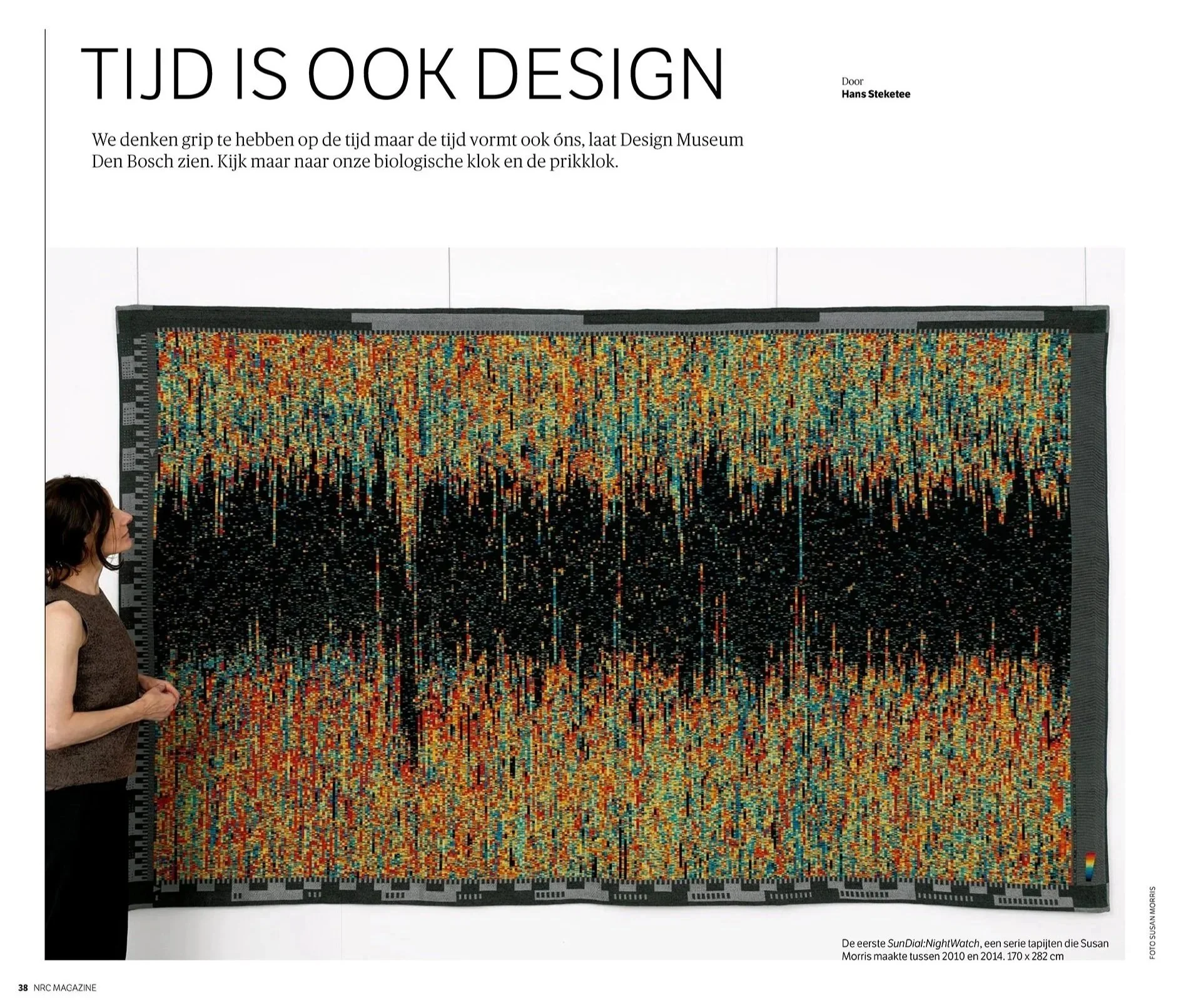

The Actiwatch is a wristwatch used in biorhythm research. It records levels of natural and artificial light, and how active you are. British artist Susan Morris wore one for five years and used the data as input for a Jacquard loom, which can weave complex patterns by machine. She assigned red thread for high activity, black for little or no activity, and blue for “awake but not very active.” You can see quite a bit of that blue thread in the tapestries from her SunDial:NightWatch series, made between 2010 and 2018. “I was probably sitting at my computer then,” she said about it. Morris’ art reflects the opposite of what happened in Siffre’s cave. Her internal clock is constantly synchronized, tightly regulated, with no chance to run free. Her tapestries, she says, depict “someone living in a Northern European city during a period of high capitalism, […] a body trapped in artificial structures like clock and calendar time, public transport schedules, 24/7 work practices, light pollution, and the insomnia that comes with it.”

One of the tapestries from Morris’s SunDial:NightWatch series will be on display from April 5th at the Design Museum in Den Bosch. The exhibition, All the Time in the World, opens with an Egyptian sundial — two sticks with a string. SunDial:NightWatch_Light Exposure 2010-2012 (Tilburg Version), 2014, a Jacquard tapestry measuring 155 x 360 cm, is the last of hundreds of objects that together show how we try to understand, track, control, and shape time — because time is also a form of design. And how time takes hold of us, invades our lives, and shapes us.

Kairos rarely reveals himself — sometimes just at the edge of your vision, and when you turn your head, he’s gone. Chronos is always present. Time that ticks along in the phones, microwaves, cars, and laptops that surround us, in the global standard time that stock exchanges follow, and the satellites of the Global Positioning System (GPS). But Siffre’s adventure shows that Chronos has his whims too. Operation Desert Storm, which ended the Iraqi occupation of Kuwait in 1991, also marked the breakthrough of GPS. Satellites transmit precise time signals from 20,000 kilometers above Earth. By comparing them, a receiver on the ground can accurately determine its position. The system was mainly intended for navigation at sea and in aviation. But for American ground troops trying to find their way in deserts, amidst sandstorms and without reliable maps, GPS turned out to be a lifesaver. American four-star General Norman Schwarzkopf, who led the operation, also compared time signals. He wore two wristwatches: one set to the time in Saudi Arabia, where his headquarters was, and the other on Eastern Standard Time (EST), so he could instantly see what time it was in Washington, D.C.

Knowing the time in another time zone is now as unremarkable as ubiquitous GPS. But in the 18th century, that too was a revolution. The invention of a clock that could stay synchronized with Greenwich time — even on a swaying ship — made it possible to know what time it was ‘now’ here, and with a bit of calculation, where ‘here’ was. That’s why it’s fitting that in Den Bosch you can see a photo of ‘Stormin’ Norman’ with his two Seikos, along with a ship’s chronometer from 1860, with its brass workings in a mahogany case, built by McGregor & Co, clockmakers for the Admiralty. Until well into the 19th century, nearly every Dutch city had its own local time. The station clock, needed for a reliable timetable, pulled the time tight across the country, just as the telegraph did for the world. But the limitations of mechanical clocks clashed with the growing need for ever more accurate and stable ‘universal’ timekeeping for navigation, communication, and science.

In 1923 it was discovered that a piece of quartz crystal could serve as the heart of a clock by making it vibrate. This vibration was so stable that it deviated by only a few seconds per month, compared to several seconds per day for the best mechanical clocks. For some scientific applications, even the quartz clock wasn’t accurate enough. Enter the atomic clock, from the mid-20th century, with a deviation of one second every 300 years — a figure the latest atomic clocks now laugh at. Universal Time (UT) was originally based on the Earth’s rotation. But that movement isn’t constant and is gradually slowing. Atomic clocks fall out of step with astronomical time. It’s a matter of fractions of fractions of a second, but as Simon Garfield wrote in Timekeepers (2016), a book about our obsession with time: “if nothing were done, after hundreds of thousands of years the sun would set during lunch.”

That’s why atomic clocks have to be periodically corrected with a leap second. It also led to a new definition of the second by the Bureau International des Poids et Mesures. Since 1968, it’s been defined as the duration of 9,192,631,770 vibrations of a cesium-133 atom in a resting state — and no longer a precise fraction of the average day in 1900. The deadline for this article fell before the opening of the All the Time in the World exhibition. So this article is also a glimpse into the future. When I visited Den Bosch to speak with curator Tomas van den Heuvel, there was still nothing to see — except a wall of post-it notes with different themes (‘Observation’, ‘Standard’, ‘Capital’, ‘Meaning’) and photos of the objects that will be exhibited. They’ll be displayed on ‘islands,’ each with its own theme, with a pattern of lines on the floor where each island seems to press down, a reference to the curved spacetime from Einstein’s general theory of relativity, which among other things says you cannot separate ‘here’ and ‘now.’ I would have loved to already see, for example, the wadokei, a Japanese pendulum clock that can indicate varying day lengths in winter and summer. And the Bundy clock from 1890, an early punch clock that shows how time became money. And of course, amid everything that ticks, vibrates, turns, swings, and pulses — the Calendar of Your Life, a video about a board with 5,200 boxes: the number of weeks a centenarian ‘has’. That calendar was made by Kurzgesagt, a German platform that uses animations to explain complex science. It’s at once a sobering memento mori, a classical reminder that everything fades and ultimately steps outside of time.

Marloes Heineke